The Case for Greater Palestine

Draw Outside the Sykes–Picot Lines

“The River Jordan, it is true, marks a line of delimitation between Western and Eastern Palestine; but it is practically impossible to say where the latter ends and the Arabian desert begins.” — 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica

“This Arab country belongs to all, Jordanians and Palestinians alike. When we say Palestinians we mean every Palestinian throughout the world, provided he is Palestinian by loyalty and affinity.” — King Hussein of Jordan, 1972

“We are, after all, twin brothers, Palestine and Jordan.” — Yasser Arafat, President of the Palestinian Authority, 1999

Western countries like France, Australia, Canada, and the UK have now recognized a Palestinian state. But as legal scholar Guglielmo Verdirame notes, Palestine lacks the basic prerequisites of statehood, including defined territory and effective government. Does it include all of the West Bank and Gaza, even though previous statehood negotiations involved land swaps? Does it include Israel proper (minus its citizens), as most Palestinians would like? Is it ruled by the Palestinian Authority (PA), the corrupt government in parts of the West Bank, or Hamas, which is still nominally in charge of Gaza? Why not recognize two Palestinian states, one for each territory? This line of questioning points to the fundamentally unserious, symbolic nature of premature statehood recognition. But it also points to issues that need to be resolved if there is ever to be some measure of stability and peace in the Holy Land. As President Donald Trump once correctly noted, “If you don’t have borders, you don’t have a country.” Palestine has no borders, so it isn’t a country. But Israel’s borders are also inchoate. The unresolved status of the Palestinian territories is a sieve straining the Jewish state’s legitimacy—a process annexation would only accelerate by formalizing the demographic formula for civil war: a half-Arab, half-Jewish state with a sliding scale of legal rights.

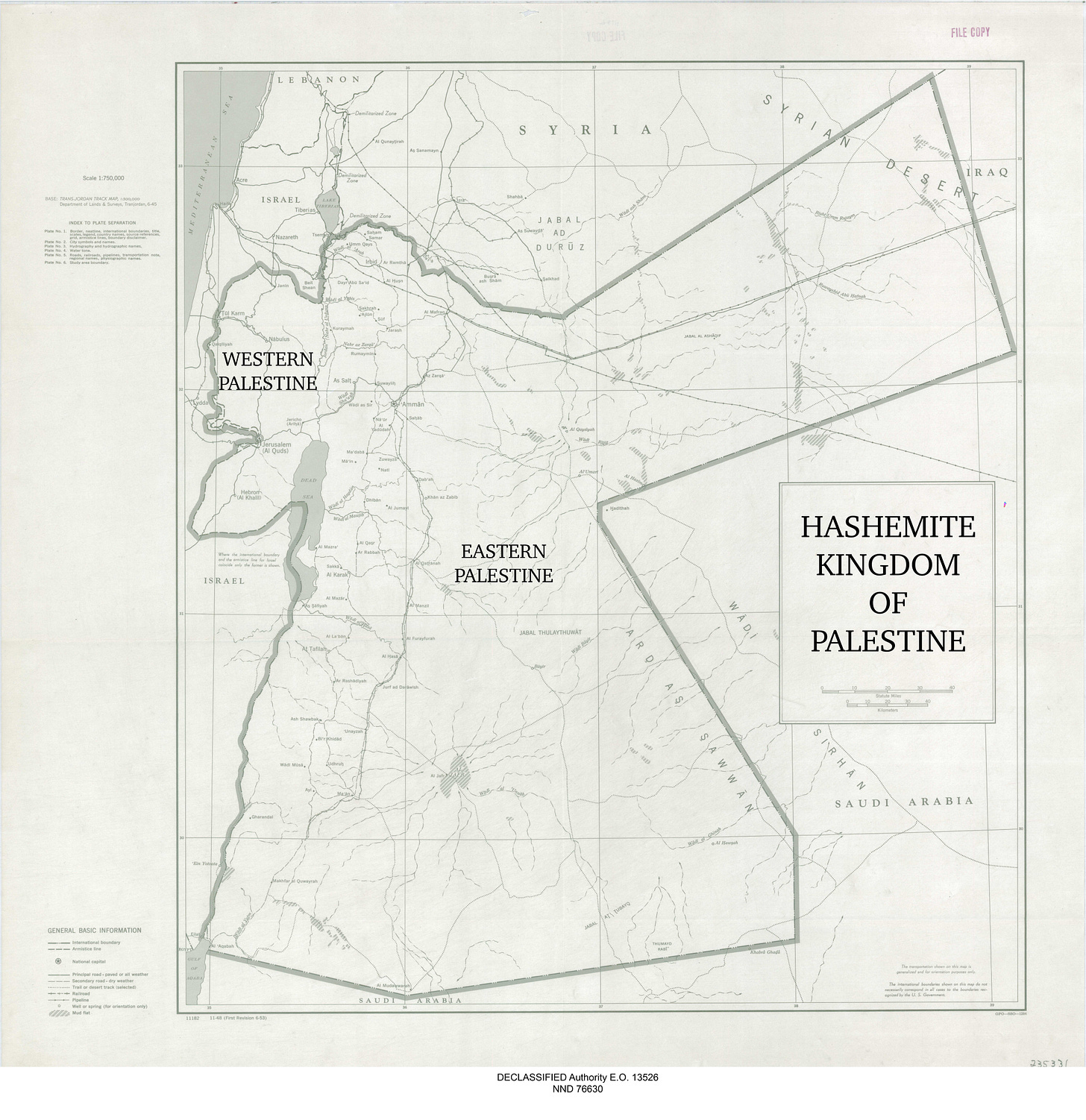

Fortunately, there is an alternative political authority for the Palestinians, one with a proven track record of effective governance: the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. After the fall of the Ottoman Empire in World War I, Jordan itself was initially part of the British Mandate for Palestine. Even the term “West Bank” refers to Jordan, which is the corresponding “East Bank” of the Jordan River. The Jordanians controlled the West Bank following Israel’s 1948 War of Independence, and formally annexed the territory in 1950. In 1954, Jordan granted full citizenship to Palestinians residing in the West Bank, as well as to Palestinian refugees who had migrated to Jordan proper. This is in stark contrast to other Arab countries like Syria and Lebanon, where Palestinians are denied citizenship under the delusional assumption that they will one day march back into Israel. Jordan lost the West Bank to Israel after it foolishly joined the 1967 Six-Day War. However, Jordan only officially gave up its claim to the territory in 1988, in deference to Yasser Arafat’s Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). Even still, at least half of Jordanian citizens are of Palestinian descent, giving Jordan a demographic as well as historical claim to the title of Palestinian state. Why not make it official by reclaiming the West Bank (plus Gaza, which was formerly controlled by Egypt1) and becoming the Hashemite Kingdom of Palestine? The West Bank could be renamed Western Palestine, while Jordan could become Eastern Palestine, as it has de facto been.2

The strongest Israeli argument against Palestinian statehood is based on security. Israel fully withdrew both its military and settlers from Gaza in 2005. After winning elections in 2006, Hamas seized Gaza from the PA in 2007, turning the Strip into a terror base for rocket attacks on Israel. For many Israelis, the October 7 massacre was final proof that any Palestinian state would only be a launching pad for irredentist aggression. In the West Bank, Hamas is more popular than the Fatah party that dominates the PA, which itself has a history of terrorism against Israel. At Israel’s narrowest point, the country is only about nine miles wide from the West Bank to the Mediterranean, with major population centers near the coast. Israelis rightly worry that, absent their military presence, the West Bank would become a larger, more existentially dangerous version of Gaza. Would an independent Palestine be willing and able to curtail Hamas? Perhaps if it were headed by the Hashemite rulers of Jordan. After all, Israel and Jordan signed a peace treaty in 1994, are both American allies, and share a mostly quiet border. Jordan has formally banned the Muslim Brotherhood, ideological kin to Hamas; shot down Iranian rockets aimed at Israel; and expelled PLO terrorists in the 1970–71 Black September conflict. Aren’t three decades of peace (plus surreptitious cooperation before that) a good indication that Jordan can be trusted?

Of course, a Jordan that includes the West Bank and Gaza would have a larger Palestinian population, many of them radicalized. Although the West, Israel, and friendly Arab nations could provide the Hashemites with security and financial backing, there is a chance that Palestinian extremists could overthrow the monarchy and use their newly won territory to attack Israel. Fortunately for Israel, it has defeated Jordan in previous wars and could certainly do so again. The 1979 Egypt–Israel peace treaty made Israeli withdrawal from Sinai (conquered in the Six-Day War) contingent on Egyptian military restrictions backed by multinational monitoring. Similar terms could be applied to the West Bank and Gaza. Moreover, the appearance of legitimacy matters. A Palestinian state attacking Israel—absent arguments about occupation, settlements, and apartheid—would be a clear-cut case of unprovoked aggression for most of the civilized world. The greatest security threat to Israel isn’t conquest by the feckless Palestinians. It’s a loss of American support due to isolationist sentiment on the right and pro-Palestinian sympathy on the left. By separating itself from the Palestinians and seizing the moral high ground, Israel could at least regain a measure of support from the center-left, if not fanatical anti-Zionists. A settlement of the Palestinian issue would also open the door to an expansion of the Abraham Accords, most notably to a normalization agreement with Saudi Arabia. Greater regional integration would make Israel less reliant on America in the first place, which would consequently increase its support (or at least mitigate a growing hostility) among the “America First” right.

Besides the Israeli security argument, there is also the religious-nationalist case for holding on to the Palestinian territories. Namely, that the West Bank and Gaza were historically Jewish and are religiously part of the Holy Land. But in the Iron Age, Gaza was home to the Philistines, ancient rivals of the Israelites, from whom the term “Palestine” is derived. Though Gaza has a long, if fragmented, Jewish history, it was only intermittently ruled by Jews and never the core of an Israelite or Judean polity. Religiously, Gaza isn’t even universally considered part of the Land of Israel, and lacks major Jewish holy sites. The West Bank—or to use the Biblical nomenclature, Judea and Samaria—is a different story. This land is indeed holy and historically significant to Jews. Likewise, Kosovo is significant to Serbs, Ukraine is significant to Russians, and, of course, Jerusalem is significant to Muslims. Political borders do not always—cannot always, due to the nature of conflicting claims—line up with a nation’s ideal territory. Israelis can visit Jordan today as tourists, and should likewise be guaranteed the right to visit Western Palestine as pilgrims. As for Israeli settlers, most could remain in Israel through negotiated land swaps, others could be evacuated in exchange for compensation, while a minority might choose to take their chances and become Jewish Palestinians.3 In his Jordanian–Palestinian confederation proposal, billionaire businessman Hasan Ismaik even suggests that Jewish settlers be granted a quota in Jordan’s parliament.

What’s in it for Jordan? First, it’s worth recalling that Jordan, like Palestine, was never historically a distinct country. Following World War I, the British carved Palestine out of the Ottoman Empire, and then Jordan (at the time, Transjordan) out of Palestine. Transjordan was awarded to the Arabian Hashemite dynasty for their service during the “Great” Arab Revolt, though T. E. Lawrence played a larger role and probably should’ve been given the kingdom instead. Palestinian and Jordanian Arabs speak the same language (Levantine Arabic), practice the same religions (mostly Sunni Islam, with a Christian minority), and are ethnographically indistinguishable.4 Between the time of the Crusader states (1099–1291 CE) and the mid-20th century, they’ve also always been under the same imperial authority. Uniting Jordanians and Palestinians in a single state would therefore be a return to the historical norm. By reclaiming sovereignty over the West Bank, the Hashemites would gain more land and subjects (many highly educated), which monarchs generally find desirable. They’d also win access to the Mediterranean via the Gaza exclave, which would be a lifeline for their mostly landlocked nation. While Jordan’s rulers are currently loath to reinsert themselves directly into the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, they’d likely be willing to do so as part of a regional agreement in partnership with Palestinians.

The most fanatical Palestinian irredentists will never relinquish their dream of seizing all of Israel. But a substantial number of pragmatists may welcome a seriously presented alternative to the current hopelessness of their national cause. In order to capitalize on Palestinian pride, the unified state should be framed not as the Jordanian annexation of Palestine, but as the formation of a Greater Palestine. Ideally, per Saudi analyst Ali Shihabi’s proposal, it would indeed be called the Hashemite Kingdom of Palestine, but Ismaik’s Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan and Palestine option is also acceptable if unwieldy.5 Most important is that “Palestine” be included in the name of the country, so that a critical mass of Palestinians feel that their national aspirations have been fulfilled. Jordan’s king is already the custodian of Jerusalem’s Muslim and Christian holy sites (and married to a Palestinian), but should also formally adopt the title King of Palestine. Palestinian refugees elsewhere in the Arab world should be granted citizenship in the kingdom, thus universally ending Palestinian statelessness. Jordan isn’t exactly a democracy, but neither is the PA-run West Bank (let alone Gaza under Hamas rule). By joining up with Jordan, Palestinians would achieve parliamentary representation, the accoutrements of statehood, and, perhaps most significantly from their perspective, rule by fellow Arabs instead of Jews. They’d also have a state much larger than Israel, rather than two rumps barely visible on a map, so plenty of land with which to exercise their “right of return.”

The key to resolving the Israeli–Palestinian conflict is to think outside the box of historically contingent, imperially drawn Sykes–Picot borders. Contra common usage, there is no coherent “historic Palestine” (except, perhaps, Gaza). The ancient Greeks used “Palestine” to refer to the land of the Philistines (whom they knew as a fellow Aegean-origin people) in Gaza and Israel’s adjacent coastal strip.6 Subsequent to the Philistines’ 6th-century BCE disappearance, Palestine was a vague geographic expression, only given political form when the Romans renamed Judea following multiple idiotic Jewish revolts.7 Palestine was never an independent nation, and, for most of the region’s Muslim history, wasn’t even the name of a distinct province.8 Yet thanks to British mapmaking and a peculiar dialectic with Zionism,9 an Arab population now identifies as Palestinian—and their cause has acquired religious salience within the Arab and Muslim worlds, as well as the global left. If the old two-state solution is dead, but the Palestinians can’t expel the Israelis, Israel can’t expel the Palestinians, and the status quo is untenable, then we need bolder alternatives.10 Rob Malley and Hussein Agha, an American and a Palestinian involved in previous peace negotiations, have recently floated the old-new idea of a Palestinian confederation with Jordan. Other advocates include former US Deputy National Security Advisor Elliott Abrams, former Israeli National Security Council head Giora Eiland, Prince Hassan bin Talal of Jordan, Ian Bremmer of the Eurasia Group, and the late Israeli Prime Minister Shimon Peres. Per Agha, “What we have here is a biblical conflict. Biblical conflict needs prophets. It does not need diplomats.” Accordingly, as Isaiah once foretold, may all nations stream to Mount Zion to walk in the paths of the Lord, including the Hashemite Kingdom of Palestine.

Theoretically, Gaza could also be joined to Egypt, to which it is contiguous. However, there is a strong case for uniting Gaza, the West Bank, and Jordan into a single country. Namely, the Palestinians now share a political identity, so it’s logical to unite them in the same polity; Jordan previously granted citizenship to Palestinians, establishing a historical bond, whereas Egypt only administered Gaza militarily; and Jordanians and Palestinians are more closely related than Egyptians and Palestinians (eg, Egyptians speak a different dialect of Arabic).

The Israeli right sometimes argues that, because of its Palestinian population, Jordan already functions as the Palestinian state and Israel shouldn’t have to give up territory. But though Jordan is home to perhaps 3 million Palestinians, a greater number (5.5 million) live in the West Bank and Gaza. There are also 2.1 million Israeli Arab citizens, many of whom identify as Palestinian. Therefore, demographically speaking, Greater Israel would be more of a Palestinian state than Jordan. To avoid becoming Palestine, Israel needs to divest itself of Palestinian-majority land and let Greater Jordan (ie, Greater Palestine) assume that glorious title.

See, for example, the views of Menachem Froman, the late chief rabbi of Tekoa in the West Bank: “[W]hat matters is the holiness of this land. I prefer to live here in a future Palestine than leave to live in an Israeli state.”

Palestinians themselves have made similar observations with reference to the broader Arab Levant. For example, the 1919 Arab delegation from Palestine to the Versailles Peace Conference submitted a formal petition to join Syria: “We consider Palestine as part of Arabic Syria as it has never been separated from it at any time. We are connected with it by national, religious, linguistic, natural, economical and geographic bonds . . . In view of the above we desire that our distinct Southern Syria or Palestine should not be separated from the Independent Arabic Syrian Government.”

It works well enough for Bosnia and Herzegovina, so to each their own.

In his Histories (~430 BCE), the Greek historian Herodotus mentions the “Syrians of Palestine” (who served in the Persian king Xerxes’ army) as practicing circumcision and having crossed the Red Sea. In all likelihood, then, he was referring to Jews. Since the Philistines ceased to exist, “Palestinian” was a geographic marker, not an ethnonym, and could be applied to Judeans (as indeed it was, into the modern era).

The Jewish decision to take up arms against the world’s mightiest empire not once, not twice, but thrice, is proof that the Jews’ vaunted high IQ is a post-exilic development.

When the Arabs conquered the Holy Land from the Byzantines in the 7th century, they kept the Roman name Palestine for a small military district (Jund Filastin). It did not cover all of Israel and, notably for the present discussion, extended into modern Jordan. This administrative unit ceased to exist after the late 11th century.

The modern revival of the term “Palestine” is an example of what the left might call Western cultural imperialism. Per historian Bernard Lewis:

In the Middle Ages, Christian writers had usually spoken of ‘the Holy Land,’ or even of Judaea. The Renaissance and the revival of interest in classical antiquity gave a new currency to the Roman name Palestine, which came to be the common designation of the country in most European languages. European influence brought it to the Arabic-speaking Christians, the first of the country’s inhabitants to be affected by western practices and usages.

According to the 1968 Palestinian National Charter: “Palestine, with the boundaries it had during the British Mandate, is an indivisible territorial unit.” But in 1919, British Prime Minister Lloyd George declared that British Palestine would be “defined in accordance with its ancient boundaries of Dan to Beersheba,” which is in turn a reference to the Hebrew Bible. Thus the Palestinian national movement is, in a roundabout way, based on the Torah.

Perhaps Israel could expel all the Palestinians, but at the catastrophic cost of a likely irreparable rupture with the West (including the United States, not just ineffectual grandstanders like Canada), moderate Arab states, and much of world Jewry, plus a possible internal Arab uprising and civil war.

Do you think a “Jordanian option” with almost all of the West Bank—and perhaps Gaza—moving back under Jordanian sovereignty would be politically palatable in Israel? No more dreams of annexation? No more Jordan Valley security perimeter?

Or does Israel annex large portions of the territory of Area C, including the Jordan valley, with the Palestinians to be annexed in Areas A & B into Jordanian “settlements”?

The Palestinian side would probably insist on more formal “custodianship” of the Haram al-Sharif area as under the Waqf.