The Nation is Bigger Than Your Faction

Even If You Call Yourself a Nationalist

According to French nationalist leader Marine Le Pen, “There is no more left and right. The real cleavage is between the patriots and the globalists.” Populists worldwide promote the same dichotomy, which pits sovereignty against multilateralism, national identity against open borders, and economic protectionism against free trade. But there’s another cleavage that populists rarely emphasize: the one between patriots and factionalists. Historically, the biggest threat to the nation has come from disunity, which may degenerate into civil war, ease the way for foreign conquest, or simply spiral into collective decline. From the start, most nations were formed out of rival factions or tribes, and are at constant risk of fragmenting into their constituent parts. Insofar as populism itself descends into factionalism, it can no longer claim the mantle of patriotism. Instead, it becomes anti-national nationalism, an “enemy within” precisely because of its overriding fixation on enemies within.

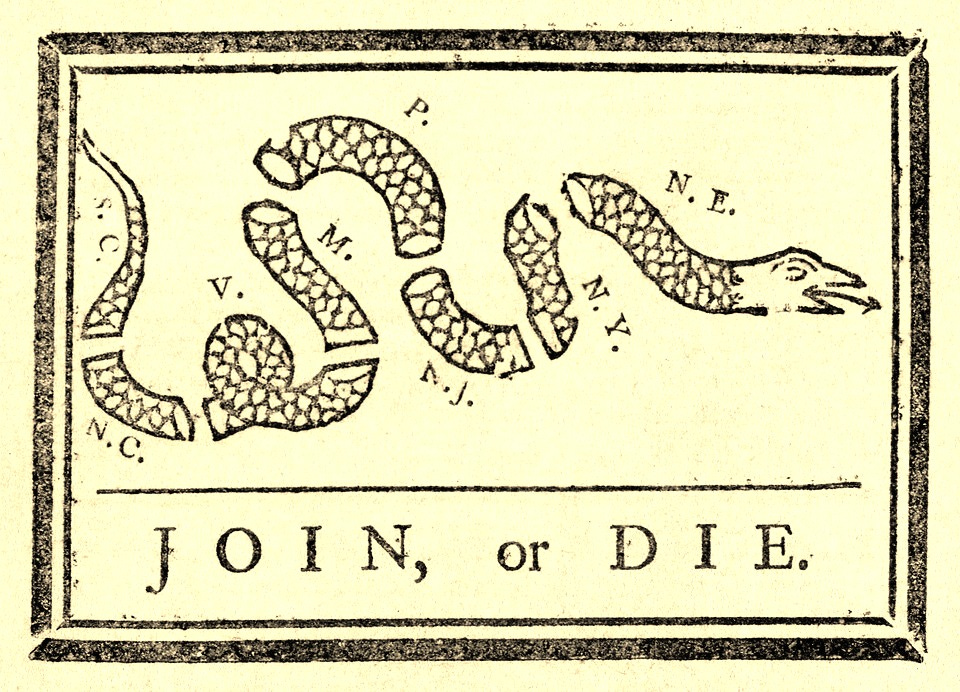

America’s Founding Fathers warned of the dangers of factionalism. For George Washington, whose family had fled England to avoid its civil wars, factions put “in the place of the delegated will of the nation the will of a party.” They “may now and then answer popular ends,” but are likely “to become potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people and to usurp for themselves the reins of government, destroying afterwards the very engines which have lifted them to unjust dominion.” James Madison, too, warned of “the violence of faction,” which he defined as “a number of citizens, whether amounting to a minority or majority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adverse to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community." Ultimately, of course, America had its own civil war; prior to which Abraham Lincoln prophesied, quoting the Gospels, that “A house divided cannot stand.”

Nationalism vs Factionalism

In Plato’s Republic, Socrates says that “the term employed for the hostility of the friendly is faction, and for that of the alien is war.” Conflict between Greeks and barbarians should bear the name war. However, inter-Hellenic conflict is best described as factional strife, since Greeks are each other’s kin. In Plato’s utopian city, the citizens “will not, being Greeks, ravage Greece or burn houses,” but instead only “treat barbarians as Greeks now treat Greeks.” Yet, as scholar Hans Kohn notes, despite such pan-Hellenic ideals, “political nationalism remained unknown to the Greeks; their loyalty was due first and foremost to the city-state, which very often found itself in the most bitter warfare with other Greek city-states, and allied or thought of allying itself with non-Greeks against other Greeks.”1 Thus while Aristotle writes that Greece is “capable of ruling all mankind if it attains constitutional unity,” such unity never came to pass. The Greek city-states banded together to fight off Persian invaders, and influenced great foreign empires (the Macedonians and Romans), but were too fractious to form a lasting polity of their own.

History is riddled with the negative consequences of national disunity. Circa 930 BCE, ancient Israel split into two smaller kingdoms, Israel and Judah, both of which were ultimately conquered by stronger empires: the Assyrians (722 BCE) and Babylonians (586 BCE). Later, the doomed Great Jewish Revolt (66–74 CE) was as much a Jewish civil war as a revolt against Rome. As Josephus writes, “Between advocates of war and lovers of peace there was a fierce quarrel. . . . Faction reigned everywhere, the revolutionaries and jingoes with the boldness of youth silencing the old and sensible. They began by one and all plundering their neighbors . . . so that in lawless brutality the Romans were no worse than the victims’ own countrymen.” The most radical Jewish faction, the Zealots, made sure that Jerusalem fought to the bitter end, which resulted in massacre, exile, and the destruction of the Holy Temple. That their doomed struggle was conducted in the name of Judaism made them no less enemies of the Jewish nation, which was ultimately wiped off the map when Judea was renamed Syria Palaestina in 135 CE after the Second Jewish Revolt.2

As an ideology, the purpose of nationalism is to unite and thereby strengthen the nation. As described by Kohn: “The fatherland is superior to kings and magistrates, it embraces all classes of society, all kinds of people, rich and poor, the great and famous as well as the unknown multitudes, the adherents of all sects and religions, of all parties and convictions.”3 The French Revolution launched the age of mass conscription, as the rights of citizenship were concomitant with the duty to defend the nation. Per the 1798 Jourdan Law, which formalized the 1793 levée en masse, “Any Frenchman is a soldier and owes himself to the defence of the nation.” Napoleon’s army of the people defeated the armies of kings because it tapped the full strength of the nation. In the economic realm, historian David Landes notes that a major reason the Industrial Revolution happened in Britain is because “Britain had the early advantage of being a nation. . . . a self-conscious, self-aware unit characterized by common identity and loyalty and by equality of civil status. Nations can reconcile social purpose with individual aspirations and initiatives and enhance performance by their collective synergy.”4 By contrast, what President Donald Trump termed “shithole countries” are riven by division, so that loyalty to clan, tribe, sect, or gang supersedes a sense of common destiny.

How to Become a Shithole Country

But is Trump himself uniting the American nation? Or is he pushing it toward “shithole” status? There’s a strong case to be made that selective, legal immigration, coupled with an emphasis on assimilation, strengthens the nation. But not the historically high, often illegal mass migration that President Joe Biden allowed. In that sense, Trump’s crackdown on illegal immigration contributes to national cohesion. So does his purge of DEI programs, which emphasize race, sex, and sexual identity over a common American identity. Yet deporting illegal immigrants doesn’t require defying court orders and thereby undermining the rule of law, which is a unifying aspect of American identity. As for DEI,

observes that “conservative success in the struggle against wokeness depends on continuing to convert centrists and even liberals to the cause, and the administration’s all-or-nothing strategy risks making liberal academia sympathetic — a truly counterproductive feat.” Trump won reelection by expanding his coalition to include more Latino, black, young, and urban voters. A truly nationalist leader would seek to extend that coalition further, instead of alienating even some of his own supporters through unpopular policies like erratic, economically self-destructive tariffs.As for foreign policy, Senator Arthur Vandenberg famously said that partisan politics stops at the water's edge. Meanwhile, Trump famously said during a meeting with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, “Putin went through a hell of a lot with me. He went through a phony witch hunt where they used him and Russia, Russia, Russia, Russia. You ever hear of that deal? That was a phony. That was a phony Hunter Biden, Joe Biden scam. Hillary Clinton, shifty Adam Schiff. It was a Democrat scam.” Truly the words of a man who puts country before faction. Earlier, Vice President JD Vance demanded Zelensky say thank you, to which the Ukrainian leader replied, “I said it a lot of times, thank you to the American people.” But Vance wasn’t interested in a thank you to the American people. He was interested in eliciting praise for Trump. A true nationalist would place the country’s interests over personal feelings toward other leaders. Yet for Trump, anger at Zelensky’s lack of obeisance and an unrequited sense of camaraderie with Putin have influenced policy making. This isn’t even factionalism based on party interest; it’s factionalism based on personal pique, which then becomes the party line.

Of course, Trump supporters can point to examples of Democratic factionalism. But if you claim to be a nationalist, then you have a special obligation to care about national unity. The nation includes people who didn’t vote for you. It even includes shifty Adam Schiff, “Radical Left Lunatics,” and those much-maligned globalists. Though tempting, you can’t just deport them all to a prison in El Salvador. Trump once said, “We have the outside enemy, and then we have the enemy from within, and the enemy from within, in my opinion, is more dangerous than China, Russia, and all these countries.” But those who view their political rivals as a greater threat than foreign powers only benefit those foreign powers. China, Russia, and “all these countries” would love to see Americans view each other as enemies, because it means we’re not focused on external threats. The nation is bigger than the Trump Organization. It’s bigger than Republicans or Democrats, populists or liberals, right or left. Those who would reduce it in size, even if they do so in the name of nationalism, are not serving the nation. They’re serving their own faction, which itself may be serving the interests of just one man, and a descent into factionalism is how nations disappear.

Hans Kohn, The Idea of Nationalism: A Study in Its Origins and Background (1944), p. 153.

In the context of modern Israeli politics, the Zealots would be slightly to the left of Itamar Ben-Gvir’s Jewish Power party.

Kohn, 456.

David S. Landes, The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Some Are So Rich and Some So Poor (1999), p. 219.

Very good article, as usual. I would point out Marine Le Pen is not a nationalist, but a souvereignist, which in the European contest we could consider as a synonim for factionalist.