Communism and fascism, the great mass movements of the 20th century, are dead in their original forms. Fascism, leaving aside left-wing epithets and comment sections, died after losing a war in 1945. Communism, leaving aside state-capitalist parties and faculty lounges, died when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. Nevertheless, the revolutionary energies that gave these ideologies life still percolate, often taking strange and parodic forms. A case in point is the current political scene in the United States.

I take as my reference a 1979 essay by philosopher Leszek Kolakowski called “Revolution—a Beautiful Sickness.”1 Kolakowski, one of the great critics of totalitarianism (and an exile from communist Poland), writes that a revolution is “a mass movement which, by the use of force, breaks the continuity of the existing means through which power is legitimated. Revolutions are distinguished from coups d’etat by the participation of a significant mass of people.” The mass movement element is why fascism is considered revolutionary, while traditional right-wing authoritarianism is not.

It seems overblown to call the events of January 6 a revolution. As Kolakowski notes, the word “revolution” signifies an ideology “whose particular characteristic is the anticipation, not simply of a better social order, but of an ultimate State which once and for all will remove the sources of conflict, anxiety, struggle, and suffering from people’s lives.” Make America Great Again—which is more of a marketing slogan than a utopian vision, an impulse than an ideology—did not quite promise that much. But even if in parodic form, January 6 had something of the exuberant air of a failed, shambolic (or shamanic) quasi-revolution. Certainly, the participation of a mass of people made it more than a mere coup attempt.

Kolakowski calls revolution “a sickness of society, the paralysis of its regulatory system.” Where isolated criticism of January 6 falls short is the failure to recognize the broader sickness of society that made even a parodic quasi-revolution possible. This sickness is not at the same level as the rot afflicting, say, tsarist Russia in 1917. But obviously, the January 6 riot was not at the same level of acumen as the October Revolution, either. What should worry us is America’s underlying sickness spreading, and a cure worse than the disease—like an injection of bleach to fight COVID—gaining greater appeal, and more competent revolutionaries, as a result.

Make America Great Again did not make America great again. But as Kolakowski observes, “Every revolution needs social energies, which only broadly exaggerated expectations can mobilize, and in every revolution these hopes must be disproportionately great in relation to the outcome.” Trump is nothing if not a master of conjuring broadly exaggerated expectations. However, per Kolakowski, even if the post-revolutionary “disappointments are naturally enormous; they can, however, be survived if . . . current facts are simply evaluated differently.” Enter “alternative facts,” now supercharged by social media and artificial intelligence.

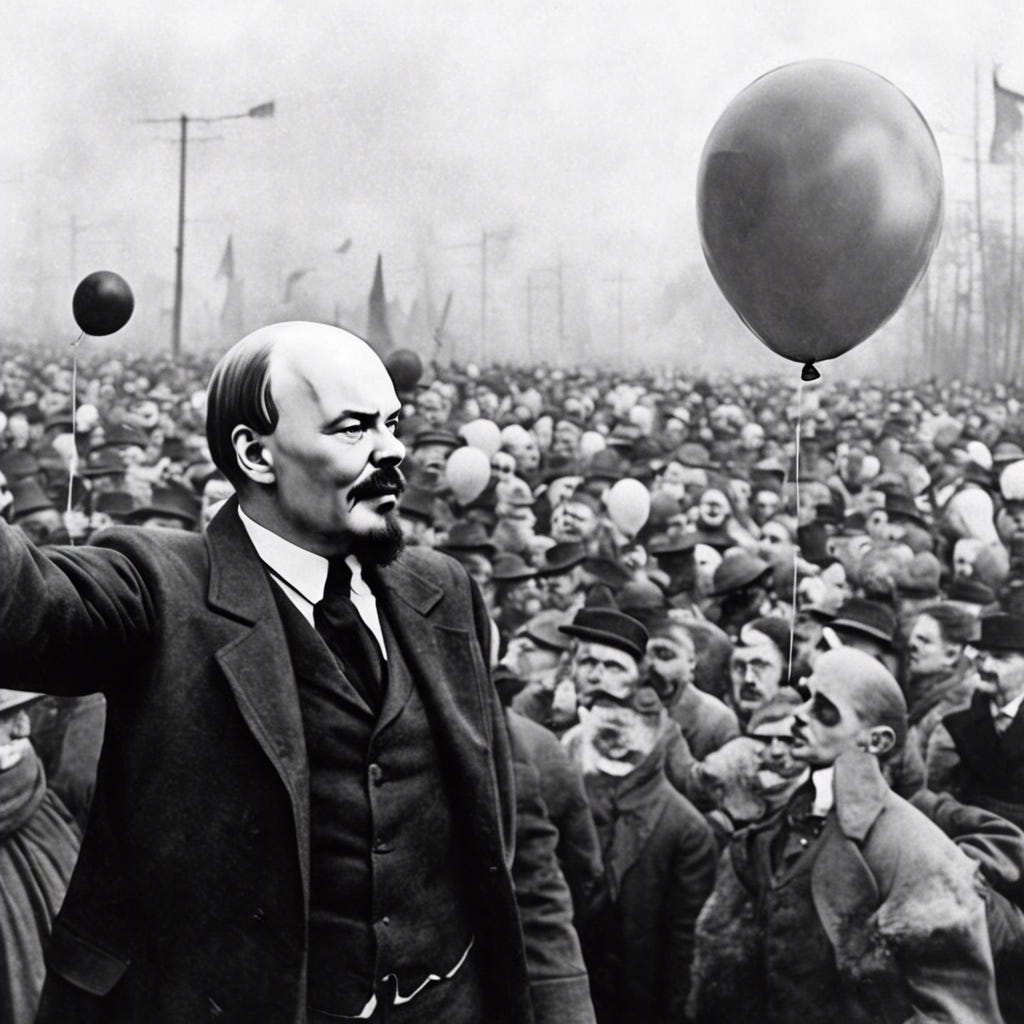

Parodic revolutionary energies power the woke left as well as the populist right. In the long run, because of generational capture, literal social-justice warriors may pose more danger of revolutionary violence than the January 6 crowd. After all, the woke left is driven by a coherent, puritanical worldview—one that, as we saw on October 7, is willing to justify the worst forms of violence—and is not merely in thrall to an opportunistic personality cult. But in the short term, in the current state of our sclerotic imperial regime, the farcical Lenin of the hour is Steve Bannon.

From his excellent 1990 essay collection, Modernity on Endless Trial.