Ideas Aren't Bound by Ideology

Of Right-Wing Socialism and Left-Wing Nationalism

An article in The Atlantic about President Donald Trump’s “right-wing socialism” provides further proof of a truism: ideas aren’t bound by ideology. Yes, per author David Graham, Trump “is embracing perhaps the most sweeping expansion of federal power since that of Franklin D. Roosevelt.”1 But earlier still, Benito Mussolini, Italy’s right-wing dictator, declared that “the spirit of [FDR’s program] resembles fascism’s since, having recognized that the state is responsible for the people’s economic well-being, it no longer allows economic forces to run according to their own nature.” In the 1930s, the New Deal was characterized by its critics as “fascism without the billy clubs.” Going further back, Mussolini began his political career by joining the Italian Socialist Party in 1900; while Imperial Germany, under conservative Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, created the first modern welfare state in the 1880s. All of this is not to say that Mussolini was a liberal or that FDR was a fascist, but that ideas travel across party lines. There’s nothing new about a right-wing nanny state (though the right may prefer to call it a daddy state).

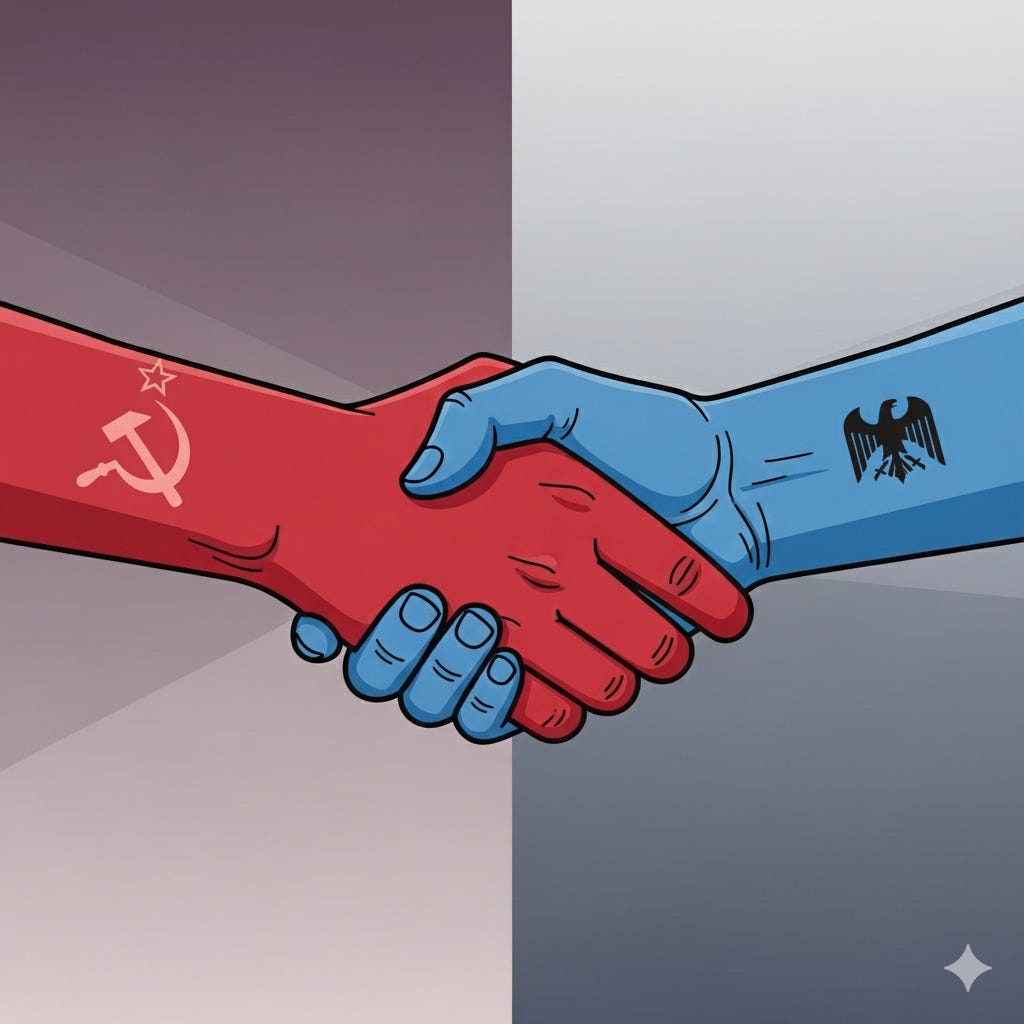

In addition to right-wing socialism, consider the overlooked phenomenon of left-wing nationalism. After the USSR failed to inspire a global revolution, Joseph Stalin promoted “socialism in one country” (not to be confused with National Socialism) and drew on Russian patriotism in the fight against Nazi Germany. (The Nazis being, of course, his former treaty partners.) Upon victory, Stalin famously toasted the Russian people as “the leading force of the Soviet Union.” Subsequently, as Benedict Anderson notes, “every successful revolution has defined itself in national terms — the People’s Republic of China, the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, and so forth — and, in so doing, has grounded itself firmly in a territorial and social space inherited from the prerevolutionary past.”2 The Chinese Communist Party is driven more by a nationalist narrative of historical humiliation and restored greatness than by residual faith in Marxism–Leninism. Notably, its official ideology is now “socialism with Chinese characteristics.” An even more extreme example of socialist–nationalist fusion is neighboring North Korea, which combines dynastic Stalinism with the race-based ideology of Juche (“self-reliance”).

Western leftists are generally hostile to Western nationalism, but idolize and romanticize “anti-colonial” national movements. For example, they demonize Zionism but adopt Palestinian nationalist symbols (British-designed flag, keffiyeh) and slogans (“From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free”; or, in the Arabic version, “From the water to the water, Palestine is Arab”). Essentially, leftists have adopted the notion of the “proletarian nation” that fascists once applied to Italy and Germany, but given it an exclusively anti-Western orientation. Just as the proletariat is the redemptive, revolutionary class in classical Marxism, proletarian nations are the vanguard of collective liberation in leftist post-fascism.3 Similarly, settler-colonial theory functions as the left-wing iteration of blood-and-soil nationalism. Thus indigenous peoples (or “people of color”) are the authentic Volk, while “settlers” (more broadly, Europeans) are their rootless exploiters. Leftist anti-Zionism is thereby seamlessly grafted onto right-wing antisemitism, with the difference being that Jews are vilified for being “functionally white” instead of oriental (“Semitic”) by nature.

The history of the term “liberalism,” now associated with the left in America, further illustrates the Magellan-like trajectory of ideas. Whereas liberals classically favored free markets, the Fabian (ie, gradualist) approach to socialism contributed to their acceptance and then promotion of a regulated economy. Historian Jacques Barzun refers to this “reversal of Liberalism into its opposite” as the Great Switch, which he traces to the turn of the 20th century. Thus while liberalism is derived from “liberty” (the quality of being free), modern liberals look to liberality (the quality of spending freely) as their ideal instead. Accordingly, conservatives—at least those with a libertarian bent—are seeking to conserve the original meaning of liberalism.4 But even these topsy-turvy definitions are increasingly unreliable. Outside of Javier Milei’s Argentina, economic arguments no longer underlie ideological debate. Instead, both left and right are largely defined by tribal identity. Ideas are now just weapons in the culture war, which sometimes erupts into real violence.

So have the terms left and right lost all meaning? Did they ever truly have one? In the narrow sense of public policy, probably not. But these archaic directions, born from the seating chart of the late 18th-century French National Assembly, do map onto recognizable mindsets. For example, according to Moral Foundations Theory, the left emphasizes care, liberty (primarily in terms of minority rights), and fairness, whereas the right upholds the additional values of loyalty, authority, and sanctity. The left is autistic when it comes these last three values, while the right will sacrifice care in their service. Libertarians focus on liberty in its right-wing sense (“Don’t tread on me”) to the detriment of the other moral foundations.5 Also useful is economist

’s notion of “the three languages of politics,” which suggests that liberals see the world in terms of victims versus oppressors, conservatives in terms of civilization versus barbarism, and libertarians in terms of freedom versus coercion.Both right and left are prone to pathology and perversion. For example, on the right, respect for legitimate authority can degenerate into worship of brute power. This is the fascist temptation, which invariably discredits, instead of reviving, traditional principles. On the left, care for an “oppressed class” may justify and excuse hatred for an “oppressor class.” And though the left is theoretically skeptical of authority, left-wing authoritarianism is an established historical phenomenon backed by psychological research. For most of his career, Stalin—a drab, secretive figure—held the modest title General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.6 Nevertheless, in the name of a doctrine of fairness,7 he and the other Communist dictators were far more oppressive than conservative regimes based on a traditional, and so limited, notion of authority. (The 19th-century slogan of Tsarist Russia, the Soviet Union’s repressive but non-totalitarian predecessor, was literally “Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality.”) The Communists were only rivaled in their murderousness by the fascists, who were themselves influenced by the Bolshevik precedent of a revolutionary vanguard using the state as a carving knife to vivisect society.

Borrowing from Thomas Sowell, the psychologist Steven Pinker provides another way to divide ideologies: between the Tragic Vision, according to which “humans are inherently limited in knowledge, wisdom, and virtue, and all social arrangements must acknowledge those limits,” and the Utopian Vision, for which “psychological limitations are artifacts that come from our social arrangements, and we should not allow them to restrict our gaze from what is possible in a better world.”8 The Tragic Vision is associated with Edmund Burke, the forefather of modern conservatism, while the Utopian Vision is expressed by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who influenced the revolutionary left. Still, there are humble forms of the left that accept the Tragic Vision (eg, Cold War liberalism), and right-wing revolutionaries with their own Utopian Vision (eg, Mussolini, who sought to create the New Fascist Man). Pinker argues that “the new sciences of human nature really do vindicate some version of the Tragic Vision and undermine the Utopian outlook,” but they won’t help us choose the correct tax policy.9

A corollary of the Tragic Vision is that neither the left nor the right will ever vanquish the other side. At least in protean form, liberal and conservative dispositions are psychologically ingrained, so they will reappear in each generation. But liberal and conservative politics, which are downstream of psychology, evolve over time and are subject to mutual influence. Thus we have the emergence of right-wing socialism and left-wing nationalism, authoritarianism on both sides, and the migration of liberal values across the political spectrum. Once we realize that ideas aren’t bound by ideology, we can, perhaps, evaluate them on their merits instead of by tribal affiliation. If you’re a woman of the left, you should still be able to acknowledge that Communism was a malevolent failure, even though it shared your passion for equality and solidarity. If you’re a man of the right, you should likewise recognize that fascism was a nihilistic disaster, despite its promotion of traditional values like hierarchy and order. From these extreme cases, perhaps we can arrive at a politics of reasoned debate and post-partisan critique despite our temperamental priors. Ideas aren’t bound by ideology, and neither are people.

Not to mention the most ambitious public health agenda since, er, Michelle Obama.

Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (1991), p. 2.

More broadly, in leftist political theology, Islam is the proletarian religion. French philosopher Michel Foucault praised the 1979 Iranian Revolution for its “political spirituality.” His affinity with Ayatollah Khomeini was based on their shared opposition to Western “imperialism,” rejection of Enlightenment modernity, and attraction to revolutionary violence. Today’s progressive Hamas sympathizers are Foucault’s ideological heirs.

Jacques Barzun, From Dawn to Decadence: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life (2000), p. 688.

See Jonathan Haidt, The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion (2012).

Stalin only officially became Premier of the Soviet Union in 1941, in the context of World War II. He adopted the military rank Generalissimo after the Soviet victory.

Steven Pinker, The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature (2002), p. 287.

Pinker, p. 293.

We need to move beyond the mind-numbing right-left dichotomy. Zeev Sternhell's iconic book about fascism is called "Neither Right Nor Left" but try to explain to college students that right-wing does not necessarily equal fascist, and left-wing does not necessarily equal liberal. The American political scene today has little to do with the Cold War binary (and even during the Cold War, this binary was mostly an oversimplification). We desperately need a new vocabulary. The classification of ideologies into Tragic Vision and Utopian Vision may be the beginning of such a vocabulary.